![]()

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||

|

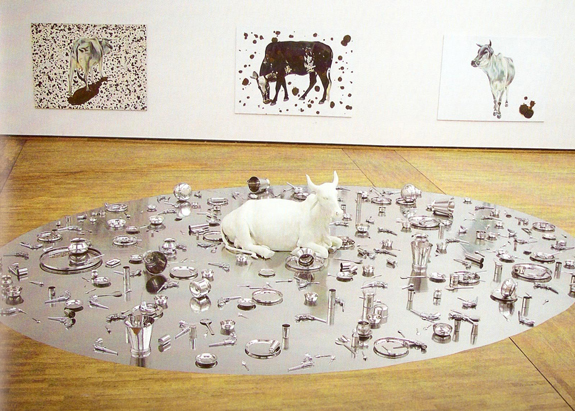

Cultures and many locales Bhavna Kakar takes a look at Subodh Gupta's works which touch the notion of culture, flowing through different locations and timeframes.

Subodh converts banal objects into icons of our ordinary

lives. He is a maker of irreverent icons. The everydayness of objects

is suddenly broken with an artistic intervention and at the same time

the aesthetical intervention is brought down to a kind of banality in

this act. With one stroke Subodh erases the distinction between the

quotidian and the aesthetical and this coalescing with ease and humor

gives a certain amount of ambiguity to the object, which now is

selected and aesthetically mediated (or re-casted through a medium

which is not 'natural' to the casted object).

Subodh Gupta's

works

portray

objects

and

images

of indecisive

moments

and

cultural

fluctuations.

During

the past

decade,

his

art has

employed certain

clichéd

emblems of

India:

the cow,

stainless

steel

kitchen articles,

the scooter,

cow dung cakes,

and his own persona

as

a man

from

a

village

in

Bihar.

All

along,

Gupta's

purpose

was

two-fold -- to both edify such emblems

and

to critique

them.

Since his aim is

dual, to

elevate and reprimand,

his penchant

is usually

for

images

and objects which

already possess

an internal hybridity

which already appear to be comically confused

themselves. In one of his works, The Way Home II of 1999, the artist placed a life-size cow, cast in fiberglass and painted white, within a circular field surrounded by a combination of steel kitchen utensils and ersatz country-made pistols. Here, violence lay camouflaged and dormant within the bosom of domesticity, the symbol of a transcendent purity inaccessible and immobile at the center. My Mother and Me was an architectonic form assembled entirely from cow-dung cakes, a Utopian structure that fused the ancient practices of the rural village with Modernism. In another work, Gupta's self-portrait painting, its background smeared with cow-dung, blinks the word "Bihari" in fairy lights, a tongue-in-cheek parody of the ambitions of the hopelessly downtrodden to actualize their "Bollywood Dreams." Saat Samundar par (Across the Seven Seas) is the title given to a series of large-scale oil paintings that capture a mid-migratory point, the no-man's-land that is the airport today. When viewing Gupta's paintings we are forced to ask ourselves if the journey is at its very beginning or is it reaching its close? Are the subjects coming, going, or hung in the purgatory of delayed departures or early arrivals? An interstitial point both in space and time, the airport signifies exhilaration and anxiety, the tedious boredom that accompanies the most extreme physical dislocation.

Gupta

paints

the

markers

of

this

transgression,

the

precious

cargo

that

accompanies

the

passenger.

As

if

to say that we

are

nothing

more

than

the

merchandise

we

drag

around

with us:

"I

Pack Therefore

I Am."

Poised upon a

wheeled trolley are

suitcases

and

packages

that

represent

a

life

condensed,

the

most

necessary

objects

(both

in terms

of

quotidian task and

emblematic

strengths)

are

swaddled

into

vinyl boxes

or

trussed

into

bulging bundles.

In

an exhibition

in

2003,

Gupta

accompanied

this

series

of

paintings

with

sculptures

of

cast-bronze

airport

trolleys

and

luggage that

had

been cast

in

aluminum,

their

preparations

agile

and

constantly

shifting

much

as

the

impulsive choreography

which

takes

place

at

the

airport

itself.

Chance

and

arbitrary

concurrence

are exploited

(all the

works being based on the artist's

own preliminary

photographs)

so

as

to

create

monuments

of a transient

nature.

Likewise,

a sculpture depicting packages hoisted

upon the

luggage

rack

of a taxi

connotes

not only tourism

and the economy

of its

infrastructure

but also the flight abroad

of

families

and

their

eventual,

perhaps

only

temporary,

return

to

India.

In

this

mix are

complex feelings of insecurity

and

aggravation,

nationalist

pride

and

materialistic

yearnings.

Gupta

cannily

spotlights

the

simple

articles

that

symbolize

a myriad

of

social

and

psychological

conundrums

such

as

these.

His

sculpture

entitled

Colgate

is

the

aluminum casts of simple sticks

of neem, herbal

wood used

for

medicinal

purposes

and

traditionally

in India

for

dental

hygiene.

According to Peter Nagy, by continuing to focus

on emblems of everyday

India,

symbols which straddle the rural and urban scenarios, Gupta flirts

with the sentimentality which still propels much of what registers as

contemporary art in India today.

What is produced, in effect,

is indigenous

Orientalism,

one that portrays

a rural ideal that is superficial and sanitized, one which serves to

widen the rift in any actual understanding

that might

take place between the cities and villages of

India

today. Subodh Gupta's project, then, is bold in its attempt to directly confront loaded points where the city collides with the village, when the contemporary cannibalizes the traditional. In the urban landscape, the doodh-wallah or milkman, replaces his bicycle with a scooter, that poor relation of the motorcycle, and slings it with the same cans of hot broth fresh from the cows' udders. Gupta dives into these contradictions greedily, enthusiastically stirring up issues relating to development and notions of progress, racism and discrimination by skin tone (as operative within India as it is elsewhere), caste-based politics, even globalization and the continuing subjugation of the Third World by the First. Gupta's formative years were spent participating in a traveling Hindi language theatre groups, as both actor and a set-designer, and this foundation has led him to experiment with forms of expression which are reminiscent of the cathartic use of the body by the Viennese Actionists. His instantaneous experiments without regard to the categories of artistic mediums and his consistent use of potent resources and symbols has been both audacious and clairvoyant within the rather stultifying arena of India's contemporary art scene. Gupta's exposure to and participation in an international art scene has only honed his perceptions of India and its culture. Meaning, both personal and collective, is mercurial and to grab hold of it for even a fleeting moment takes perseverance and insight. Bhavna Kakar is a Delhi based Curator, Consultant and Art Historian, and the Editor of Art & Deal. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- References: 1: Johnny ML, Issue no 27, Art and Deal Magazine 2: Peter Nagy, Essay, Subodh Gupta (Published by Nature Morte and Sakshi Art Gallery

Picture Courtesy - Bhavna Kakar |

||

|

© The Guild. All rights reserved. |

||